Until 1956, Dubuque's sewage flowed directly into the Mississippi River, untreated. In addition, industry like meat packing companies would discharge their waste (including grease and blood) directly into the river. A sewage treatment plant was built in 1956, and its efforts were redoubled with advent of the Clean Water Act in 1972. At that time, the WRRC's influent saw 2000mg/L of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and had an effluent of 300-400mg/L BOD. At that time, Dubuque's population was close to 750,000. The population is much smaller now, about 60,000. Currently, influent measures 300-400mg/L BOD and effluent measures just 10 mg/L BOD. Thus, the effluent from the city has greatly improved over the past 40-50 years.

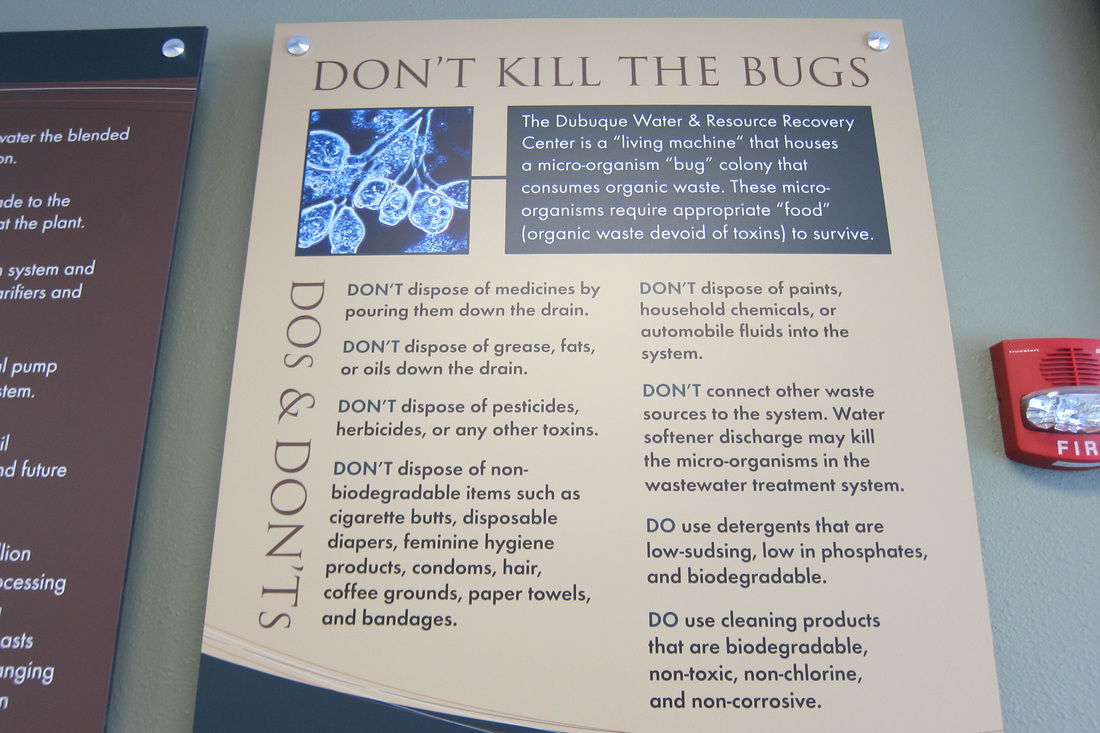

So how is this all achieved? Sewage is treated in a series of 4 pools and chambers which successively heat and then cool and stabilize the inflent rendering the material cleaner. Anaerobic digesters release methane which is cleaned and used to power micro turbines which heat 75% of the plant. This methane recovery saves $250,000 per year in electricity and reduces the plant's carbon footprint. The anaerobic digesters also yield high quality biosolid for farmland. Biosolid is very similar to compost, but comes from human waste rather than vegetable matter. Adding biosolid to the land improves the tilth of the soil, increases organic matter and allows for slow nitrogen release. Liquid effluent is water with only 10 mg/L BOD and is released into the Mississippi River.

The WRRC's goals are

#1: Improve public health

#2: improve health of the environment

#3: give back by regaining good from the process (water, energy, biosolids). WRRC is still working on decreasing the amount of N and P released into the environment, but the expensive infrastructure (they've invested $70 million and need several more million dollars to reach all their goals) only recovers and cleans so much. WRRC is hoping to eventually be able to recover phosphorous from waste water too, so that doesn't go into the river. Currently, phosphorous used in fertilizer is mined, so it has economic worth. As phosphorus is the limiting factor for algal blooms, removing it from wastewater effluent would help in decreasing the size of the Gulf of Mexico's Dead Zone. Though it must not be forgotten that phosphorous comes much more from agriculture than wastewater. Indeed, money invested upstream (decreasing N and P used in the first place) will likely be wiser and more effective in the long run.

When asked about plastics, Jonathan Brown said that macroplastics are filtered out, but that there are no microplastic filters at WRRC. Small pieces of plastic likely get rolled into the biosolids, or else exit in effluent. He also expressed his dismay for "flushable" wipes. "Yes, they're technically flushable--they will go down your toilet, but they don't break down easily and they clog our filters all the time." (Hint: Don't use "flushable" wipes!!!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed